When the only access that students of the New Testament had to most images of manuscripts was through poor-quality microfilms, interpretation of the data was rather limited. The staff at the Institut für neutestamentliche Textforschung in Münster, which boasts about 90% of all NT MSS on microfilm, instructed student collators not to try to decipher the marginalia because such were virtually impossible to read. Just the text, please. And even with the text, the students had to guess at quite a bit of the letters and words because of blurred images. Below is an illustration of the kind of images they had to work with (this is codex 2813, photographed by INTF in 1989).

Codex 2813 Microfilm Image

With digital photography, much more data can be seen and interpreted. This includes erasures, different colored ink (including the next-to-impossible-to-see-in-microfilm red and gold), smaller font, ornamentation, prickings (which are used to locate a MS’s scriptorium and age), etc. In addition, wax drippings are visible.

As innocuous as the wax drippings might seem, Henry Sanders, the editor of the editio princeps of Codex Washingtonianus, used them to show what pages were frequently on display. The reason, he argued, is that visitors would often read the pages with a candle, and less-than-careful lectors would inadvertently allow wax to drip from it onto the page.

Sanders’s comment, based on an examination of the actual MS, may have implications that go beyond codex W. With some caveats, it seems that wax drippings can be used to show what passages were favorites. If one were to examine the wax drippings seen in digital images of, say, a twelfth-century minuscule, he or she might be able to determine which passages were favorites from the twelfth century on. Of course, this kind of work would be needed to be done for a good number of manuscripts because an individual MS might be rather idiosyncratic—much the way codex W seemed to be (in that the wax drippings there, according to Sanders, only showed what passages were put on display, not what passages were otherwise favorites of readers). Lectionaries would probably be the least significant for interpreting wax drippings since they were regularly used in church services and the lector would of necessity be reading through the entire lectionary cycle, year after year. And when wax candles were used as opposed to oil lamps to read these MSS needs to be factored in as well. But MSS that were meant for study, personal use, or were otherwise not used much in public worship could contain many secrets of bygone generations of Christians.

I will offer two illustrations, one hypothetical and the other actual. John 3.16 is a favorite verse of American evangelicals today. It has even shown up on placards held by a crazed football fan wearing a multi-color afro, who would stand up in the end zone after a team scored, making sure that the TV cameras would capture the image.

But was this text that well known and that well loved in ancient and medieval times? A look at digital images of MSS might reveal the answer. Of course, in order to make one’s case, a look at the entire MS’s images would be needed to see which pages had the most wax drippings. Another caveat: if the text on a given page was reworked, scraped, or had extensive marginalia, that might be the reason for extra wax drippings, produced in this case by the scribe him/herself.

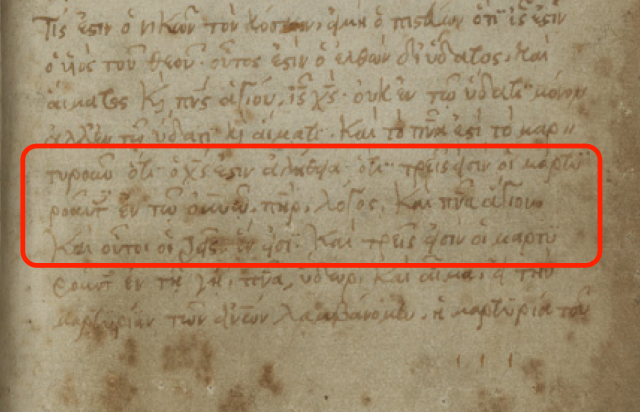

An actual illustration can be seen in codex 61, also known as Codex Montfortianus. This is the MS that was produced by a scribe in Oxford named (F)roy in 1520, which included the comma Johanneum (the Trinitarian formula at 1 John 5.7) that made its way into Erasmus’s third edition of the NT (1522). Now housed at Trinity College, Dublin, it is reported to have almost naturally fallen open to 1 John 5 because of the frequent consulting of this passage by researchers over the years. The MS nowadays is no longer available for direct consultation, but the library has produced some adequate digital images of it. And the page which contains the comma has more wax drippings by far than any other. It is also significantly dirtier than any other page, due to the constant handling of the page.

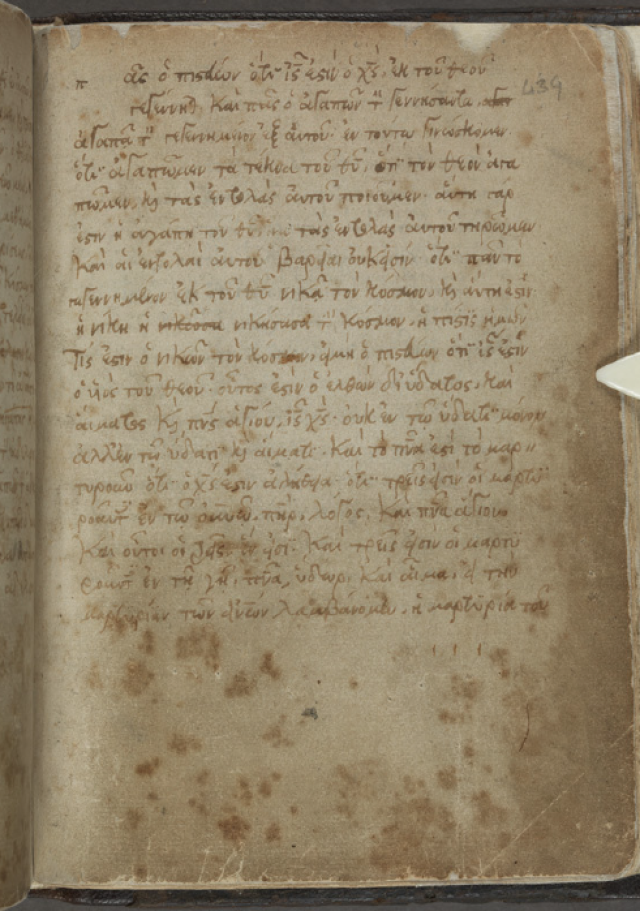

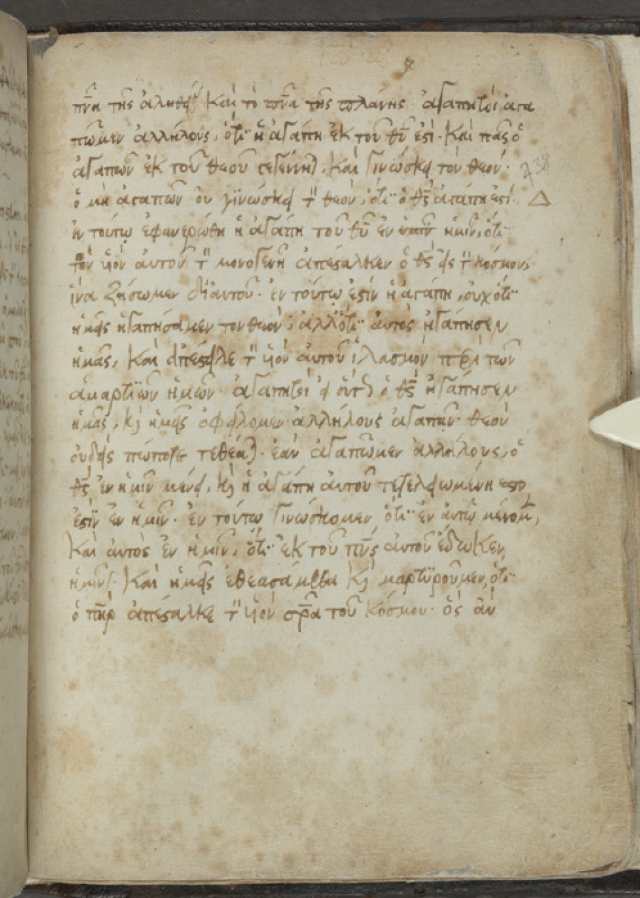

Codex 61: Two Pages before 1 John 5

Codex 61: Two Pages before 1 John 5

The Comma Johanneum in Codex 61

The Comma Johanneum in Codex 61

In the least, examining the wax drippings of digital images in continuous text MSS century by century and production-location by production-location (when known) could produce some interesting results. As these begin to be examined, certain guidelines should emerge on how to interpret the data. The necessary caveats may temper otherwise robust claims, but these should not keep students from examining the data.