The year 2024 is almost in the books. It has been a wild roller coaster ride of a year. Ironically, instability seems to be the only thing that is consistent this year. The silver lining in the nimbostratus clouds of 2024 is that the U.S. stock market has done quite well overall. And that brings me to a special invitation.

As we enter the traditional season of giving, families also use this time to evaluate their tax situation. Granted, the continually shifting tax code doesn’t make that an easy exercise. But one constant of good news is that donating securities that have been held for a year or more offers the potential for a double tax benefit—a full fair market value tax deduction and elimination of capital gains taxes.

Many non-profits now allow direct stock donations (i.e., not having to sell the stock first). If the Lord has blessed you financially, you might want to consider giving some shares to one or more charitable organizations that you support. Many such organizations are in need of large financial infusions: although the stock market has done well, the economy is still doing poorly for too many of us. Giving a gift of shares is a very tangible way to show what really matters to you without adding to your living expenses.

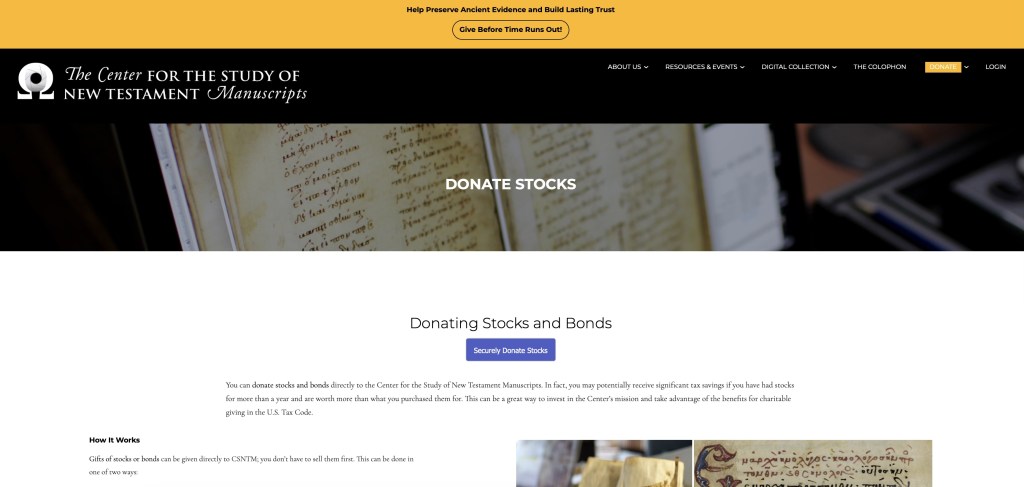

The Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts now has a “stock option” for donations. You may donate stocks and bonds directly to CSNTM without having to sell them first. Stock gifts to CSNTM are handled by Overflow, the leading giving platform for the digital age. This can be a great way to invest in our shared mission to preserve the New Testament text and take advantage of the benefits for charitable giving in the U.S. Tax Code. (Alternatively, you can use these instructions to complete the transaction with your brokerage on your own.)

I wanted to put my stock where my mouth is, so I clicked on the CSNTM “donate stocks” page https://www.csntm.org/partnership/donate-stocks and donated some stock.

Giving securities to CSNTM was a snap. It took less than 10 minutes (and I’m old and slow!) to make the donation. Overflow makes it easy.

There is some urgency for such donations, both for CSNTM and other charities. Stock donations through Overflow must be made by December 10 to guarantee posting for 2024. That’s for the guarantee; Overflow recommends giving by December 13 to almost ensure (not quite a guarantee) that the gift will be credited for 2024.

But there’s something else to consider for the long term: a donor-advised fund. Some donors like to set up their own private family foundation as a means of distributing gifts to favorite charities. But establishing a donor-advised fund with a firm like Fidelity Charitable can provide the ability to claim a higher tax deduction of 30% of your adjusted gross income compared to the 20% limit with a private foundation.

And the news gets better when you want to donate securities. By opening a giving account and contributing the shares to your donor-advised fund, you eliminate capital gains tax exposure and secure a charitable deduction based on the shares’ fair market value. Best of all, you can decide where to donate at a later date and, when the time comes, recommend a larger grant from your donor-advised fund than if you sell the shares and donate the net proceeds!

Our partner, Overflow, streamlines this process as well. You can donate from your donor-advised fund simply and securely here.

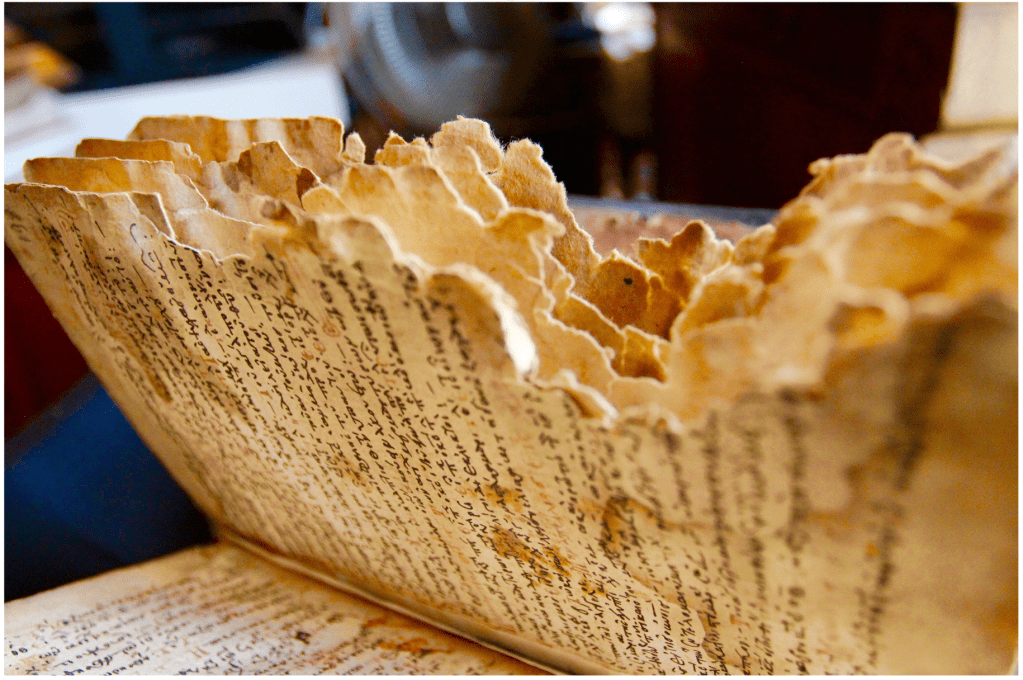

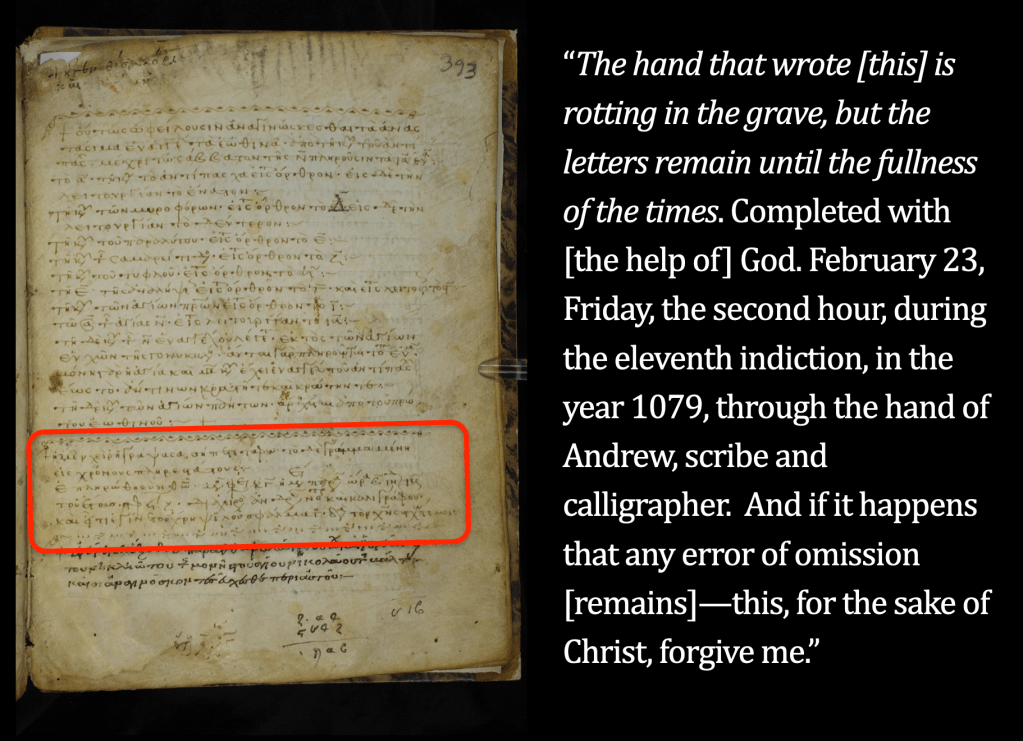

This is timely news for me and my family. I will be contributing more to my stock donations today, because I want to give CSNTM a generous Christmas present so that the Center can carry on the work that faithful scribes began 2000 years ago.