Just released from the giant publishing firm, Houghton Miflin Harcourt: A New New Testament: A Bible for the 21st Century Combining Traditional and Newly Discovered Texts, edited by Hal Taussig.

The advertisement from HMH distributed widely via email last week was not shy in its claims for the 600-page volume. The subject line read, “It is time for a new New Testament.” In the email blast are strong endorsements by Marcus Borg, Karen King, and Barbara Brown Taylor. Borg and King, like Taussig, were members of the Jesus Seminar (a group headed up by the late Robert W. Funk, which determined which words and deeds of Jesus recorded in the Gospels were authentic). King and Taylor are on the Council for A New New Testament. All of them share a viewpoint which seems to be decidedly outside that of the historic Christian faith, regardless of whether it is Catholic, Orthodox, or Protestant.

The New Books

The title of the book sounds provocative; the reality is just as much so. “A council of scholars and spiritual leaders” was convened to determine which books besides the traditional 27 should be added to the New Testament. Significantly, it’s not called a “council of scholars and church leaders” for a reason. Although, to be sure, there were bona fide scholars on the council, not all were church leaders; arguably, in fact, almost none were. The council of 19—including two rabbis—examined several ancient writings which the jacket blurb euphemistically calls ‘scriptures’ and determined which of these worthies deserved a place at the table with original New Testament books. Ten books were selected for this honor, along with two prayers and one song. The song (if that’s the right term) is called “The Thunder: Perfect Mind” and is one of the Nag Hammadi codices. There are no references to it in the ancient world; it never mentions Jesus and may, in fact, have been written three centuries before he was born. Some of the council members wanted it to be listed first in the New New Testament, in spite of (or because of?) its apparent non-Christian perspective. How it is possible for the jacket blurb to say this book was ancient ‘scripture’ when our only knowledge of it comes from Nag Hammadi staggers the mind.

Here is the list of new books added to the New Testament by this council:

- The Prayer of Thanksgiving

- The Prayer of the Apostle Paul

- The Thunder: Perfect Mind

- The Gospel of Thomas

- The Gospel of Mary

- The Gospel of Truth

- The Acts of Paul and Thecla

- The Letter of Peter to Philip

- The Secret Revelation of John

- The First, Second, Third, and Fourth Books of the Odes of Solomon

What strikes one immediately is that most of these additions seem to be of two types: Gnostic or proto-Gnostic essays and writings that exalt women. Further, what is also striking are books that did not make the cut. Among them are the Shepherd of Hermas, the Didache, the Epistle of Barnabas, First Clement, and other books in the collection known as the Apostolic Fathers. In other words, the books selected by the council were selected with an agenda in mind; they were not chosen because they ever made a serious claim to canonicity. Indeed, as was mentioned above, at least one of them is not even mentioned in any extant ancient writing.

Consider again the writings of the Apostolic Fathers. These are writings that were considered orthodox in that they offer a similar viewpoint on doctrinal and practical matters as is found in the New Testament. They are purportedly written by first-generation disciples of the original apostles, though in some cases they are another generation removed. The Shepherd of Hermas was so highly regarded in the ancient church that we have more copies of it from before AD 300 than we do the Gospel of Mark. The Muratorian Canon speaks highly of it but stops short of treating it as bearing the same authority as the New Testament books because of its known recent vintage (mid-second century). But certainly the Shepherd has far better credentials than any of the 13 newly discovered writings for canonization. That the ancient church rejected even this document is implicitly damning evidence that none of the new discoveries really belong within the pages of Holy Writ. We will revisit this issue of the ancient church’s view of authoritative writings at the end of this short review.

The Council of Nineteen and the Ancient Church Councils

The council of nineteen that is attempting to do nothing less than reshape Christianity into an image more compatible with their worldview requires some scrutiny. Who are these people and on what basis does this council have any binding authority on anyone? Most of them are professors, pastors, authors, or rabbis. I cannot say for sure, but I do not believe that any one of them would consider themselves to be orthodox in the sense of holding to the seven universal creeds of the ancient church. John Dominic Crossan and Karen King are perhaps the best known scholars in the group. All we are told about their purported authority to add thirteen writings to the New Testament (bringing the total to 40, a number which often speaks of trials and judgment in the Bible!) is that this group was “modeled on early church councils of the first six centuries CE that made important decisions for larger groups of Christians” (A New New Testament, 555). But the similarities with the ancient councils stop there. Perhaps this is why nothing more is said.

The ancient church sent representatives to the great councils who would make decisions that the churches agreed were to be binding on all. These ancient councils especially hammered out doctrinal issues. And today, all branches of Christendom embrace the decisions and viewpoints of these universal councils as at least good guidelines on what constitutes orthodoxy, if not fully authoritative. There is one key exception to this: the liberal Protestant branch of the church rejects these councils because it rejects the divinity and bodily resurrection of Christ. And the council of nineteen? I cannot speak for all of them, but a good portion of them at least are adamantly against Christ’s deity, his bodily resurrection, his atoning death, the Trinity, and that the Bible has any kind of authority in doctrinal matters.

And they certainly did not conduct their meetings in the spirit of the ancient councils. Those councils were populated by persecuted Christians, representing the major churches and sees, who came to theological decisions based on the final deposit of revelation in the New Testament. Many of them were exiled or lost their lives after the state was swept along by every wind of doctrine while the persecuted saints remained steadfast in their beliefs. The council of nineteen may claim some semblance to these ancient councils, but there is more dissemblance than semblance in the their attempted coup.

Ancient Canon Decisions

As for thinking through what belonged in the New Testament, there was no universal church council that ever made an official list. Here is another point of incongruity between this postmodern council and the ancient ones: the council of nineteen has, by its own self-asserted authority, pronounced a verdict on what goes into the New Testament. At least they did not throw out the Gospel of John, something that more than one member of the Jesus Seminar was wont to do!

Even though there was no ancient universal council regarding the New Testament canon (suggesting, in the words of Bruce Metzger, that the canon is a list of authoritative books [the Reformed view] rather than an authoritative list of books [the Catholic view]), the ancient church did follow three basic guidelines: apostolicity, orthodoxy, catholicity. These will be briefly explained below.

Apostolicity meant that a book had to be written by an apostle or an associate of an apostle if it was to be included in the New Testament. Practically speaking, this meant that any document written after the end of the first century was automatically disqualified. This is why the Muratorian Canon—the first orthodox canon list, composed in the late second century—rejected the Shepherd of Hermas as authoritative, even though it considered it to be very beneficial to Christians. Further, any book that was known to be a forgery was rejected by the ancient church. Not one of the thirteen books proposed by the council of nineteen was written by the person it is ascribed to. The ancient church would—and often did—immediately reject such books because of their spurious nature. The test of apostolicity alone thus disqualifies all thirteen newly discovered books. Relatively speaking, almost all of these newly discovered books should also be called new books.

Orthodoxy meant that those books considered for canonical status needed to conform to what was already known to be orthodox. Orthodoxy was known even before any writings were accepted as scripture. It was known through hymns, the kerygma, and the traditions passed down by the apostles. If there never had been a New Testament, we would still have enough to go on to guide us as to what essential Christianity looked like. And it looked nothing like most of the thirteen books proposed by this new council. The Gnostic and proto-Gnostic books were soundly rejected by the ancient church. And even those that were closer to orthodoxy (like The Acts of Paul and Thecla) were rejected because they failed the test of apostolicity. To put The Gospel of Thomas, The Gospel of Mary, and The Gospel of Truth into the New Testament, side by side with writings that embraced a diametrically-opposed view of the Christian faith, is unspeakably brash. And although Professor Taussig and his friends think they are doing Christendom a favor by including known heretical writings in their expanded New Testament, they are doing so at both the cost of historical integrity and pedagogical method. This can only confuse laypeople, yet even Barbara Brown Taylor—considered one of the ten best preachers in America, and thus someone who knows better than to create Chicken Littles out of the chaos that this tome will almost surely incite—has endorsed the plan and layout of this volume. Orthodoxy seemed to be the furthest thing from the minds of the New New Testament council.

Finally, catholicity was a criterion used in deciding what earned a place at the table of the New Testament canon. By ‘catholicity’ I do not mean Roman Catholicism. No, I mean that for a book to make the cut it generally needed to be accepted by all the churches. To be sure, some New Testament books struggled in this department, but not all did. In fact, within a century of the completion of the New Testament, the ancient church throughout the Mediterranean world achieved a remarkable unanimity concerning at least twenty of the twenty-seven books. This included all thirteen letters ascribed to Paul and the four Gospels. The rest would find acceptance by the fourth century, in both the eastern and western branches of the church. Most of the new additions to the New Testament fail this test miserably, too. Again, catholicity is not something that the council of nineteen considered when deciding on what books to put in. Rather, catholicity is something that this book aims to achieve. And yet it does so principally through a Gnostic-like route: by urging Christians to accept these books on the basis of their largely politically correct viewpoint, the council is seeking to reshape Christianity into something more palatable to the postmodern world, where presumably knowledge replaces faith.

(For more on these criteria, see Reinventing Jesus, by Ed Komoszewski, James Sawyer, and Daniel B. Wallace.)

Conclusion

In short, the New New Testament is a wolf in sheep’s clothing. The council that put these books forth is a farce. It has nothing to do with the councils of old, yet implicitly seeks to claim authority on the basis of concocted semblance. The books were selected by those who, though certainly having a right to scholarly examination of the Christian faith, are not at all qualified to make any pronouncements on canon. That belongs to the church, the true church. Outsiders may address, critique, and comment on the New Testament. They have that right—a right given them by the very nature of the Bible: this book is the only sacred document of any major religion which consistently subjects itself to historical inquiry. Unlike the Bhagavad Gita, the Teachings of the Compassionate Buddha, the Qur’an, or the Gospel of Thomas, the Bible is not just talking heads, devoid of historical facts, places, and people. It is a book that presents itself as historical, and speaks about God’s great acts in history, intersecting with humanity in verifiable ways. This is where orthodoxy and heterodoxy should meet, dialoging and debating over whether the Bible is in any sense true. But to suspend the discussion by a sleight of hand is both cowardly and bombastic.

Epilogue: The Value of the New New Testament

After reading the critique above, one might be tempted to ask, “Apart from that, Mrs. Lincoln, what did you think of the play?” There actually is value in this book—even, I think, for laypeople. These are important ancient books that show both continuity with the early church and discontinuity. Some are essentially orthodox; most are subchristian. But they represent how ancients perceived the Christ event and remind us that even in the early period not all ‘Christian’ groups truly embraced Jesus as the Messiah, the Son of God. Heresy is found in the earliest period of the Christian faith, too: it dogged the apostle Paul and even found a home in some of his churches after he left for other mission fields. At bottom, the question that we must all grapple with, and what many of these ancient writings grappled with, is this: What will you do with Jesus of Nazareth? That question is still the most important one that anyone can ever ask.

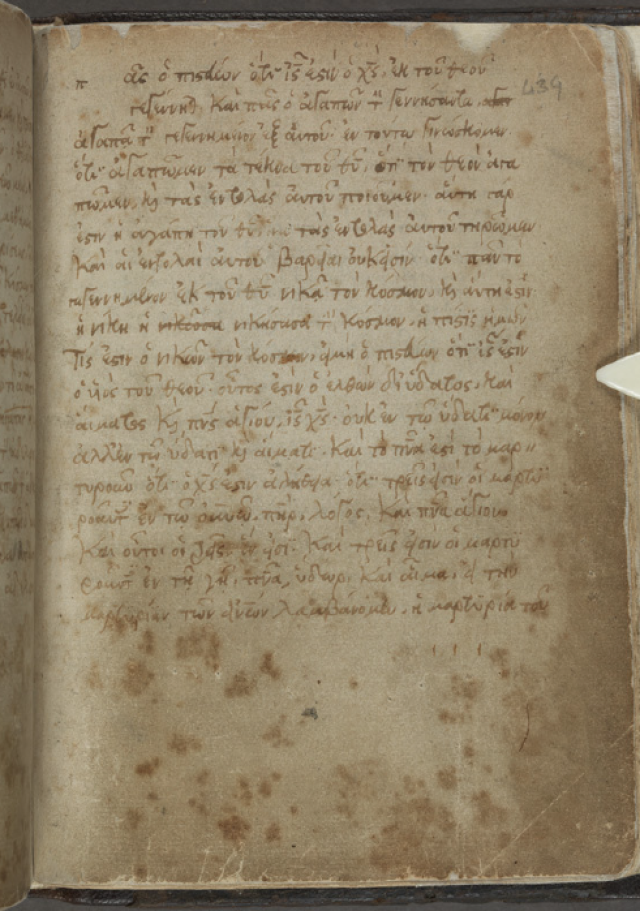

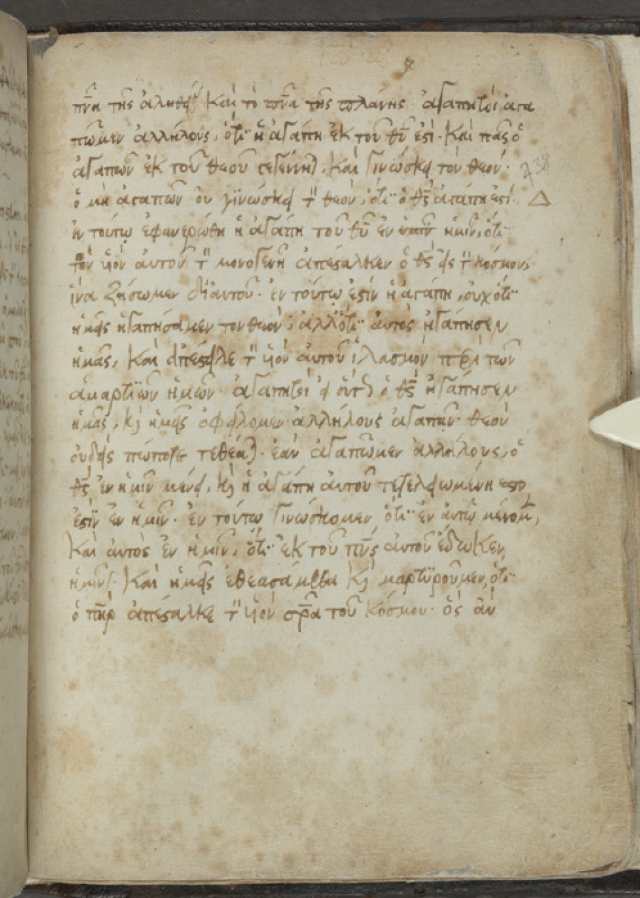

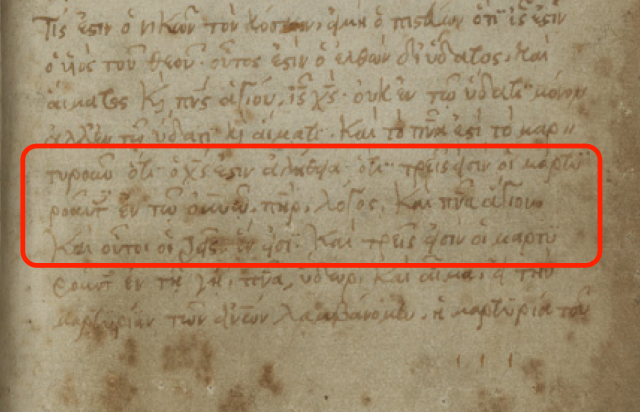

Codex 61: Two Pages before 1 John 5

Codex 61: Two Pages before 1 John 5 The Comma Johanneum in Codex 61

The Comma Johanneum in Codex 61