Anyone who has more than a passing acquaintance with ancient Greek is familiar with the venerable Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek-English Lexicon. It is a huge book, with a history reaching back more than 150 years. I have two copies, both extensively marked up—one for school and one for home. But the sheer size of the volume has sometimes caused my hand to falter. A digitized version would make my life so much easier.

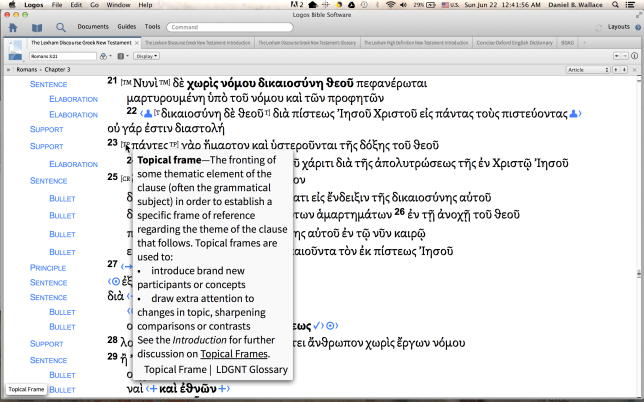

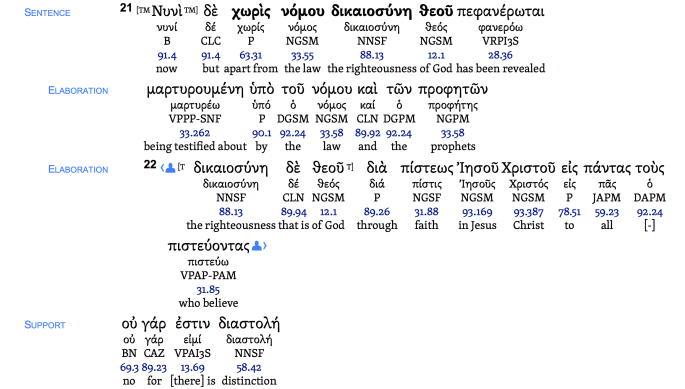

The folks at Logos apparently recognized the need of many students and digitized this standard lexicon. It seems that they have thought through everything to make it truly user-friendly. Rather than simply digitize the Lexicon, they have brought it into the electronic world in a superb way. One of the basic problems with using LSJ in print-form was that the Supplement at the back of the Lexicon needed to be consulted for a very large number of words, requiring the user to first examine the entry in the main lexicon, then see the update in the back. This two-step process has created quite a bit of inertia so that many students simply look at the main body of the Lexicon, thus short-changing themselves in the process.

The Logos version, however, has combined both sections: “Lexicon users no longer need to examine two different locations in the lexicon when studying a word that is included in the supplement. The content has been seamlessly integrated.” This alone is worth the price of the module!

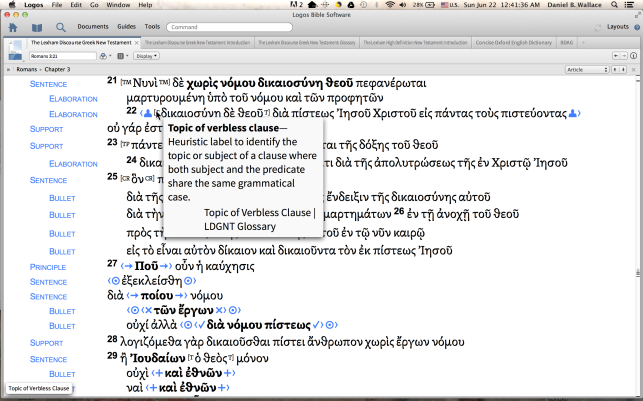

But Logos has done even more. One of the key changes has been to eliminate the hyphens in LSJ’s word entries, allowing for an easier search for a word. Other very useful search features make this tool an indispensable resource for those studying ancient Greek.

There are a few irritating features, however. Chief among them are the numerous accent mistakes on word entries. All too frequently, accents are left off words, especially adjectives and nouns. Sometimes double accents are used; other times a grave accent is found over the penult. (Some examples of these mistakes: ἀβουλητος, ἀβουλος, ἁβροβιος, ἁβρογοος, ἁβροδαις, ἁβροπηνος, ἁβροπλουτος, ἀγνωμων, ἀγορὰζω, ἀγορασμα, βᾰρῠχειρ, βαυκισμα, βεβαιωμα, ἐρῆμος, ἑτερογνης, λογογρᾰφημα, λογοποιημα, λογχοομαι, λοιμη, μαγγᾰνον, μαιευσις, οἷόνπερ, οἰστρημα). These errata definitely need to be cleaned up for later iterations. Nevertheless, the positive features far outweigh these mistakes, making this resource a goldmine of efficient, searchable data.

The module can be ordered here: https://www.logos.com/product/3879/liddell-and-scott-greek-english-lexicon?utm_source=http%3A%2F%2Fdanielbwallace.com%2F&utm_medium=partner&utm_content=productreview-3879&utm_campaign=promo-productreview