Review of David Trobisch, A User’s Guide to the Nestle-Aland 28 Greek New Testament,

SBLTC 9 (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2013). Pp. viii + 69; $25.95.

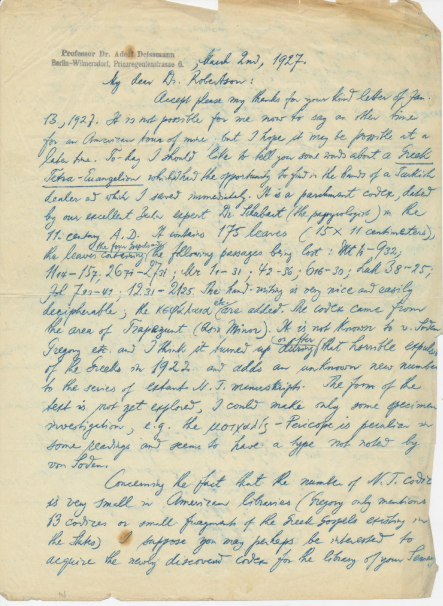

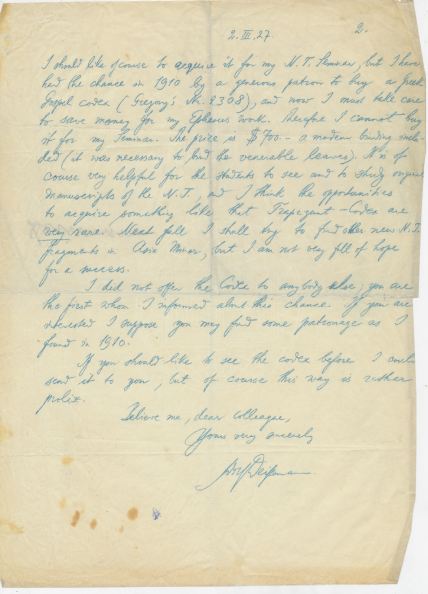

The much-anticipated publication of the Nestle-Aland Novum Testamentum Graece, 28th edition, in December 2012, instantly created a need for a user’s guide similar to what Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland’s The Text of the New Testament, 2nd edition (Eerdmans, 1989), pp. 232–60 and passim, did for the Nestle-Aland 26th edition. David Trobisch answered the call with his User’s Guide to the 28th edition, which appeared in November of 2013.

This User’s Guide however, is significantly different from the material in Aland-Aland’s Text. Whereas the latter is a scholarly introduction to (and unashamedly a promotion of) the NA26, Trobisch’s User’s Guide is significantly simpler and has only 14 pages devoted to the scholarly use of this handbook edition of the NT. The User’s Guide has three chapters (1–54) and three sections of supporting material at the end (55–69). The chapters progress in intended readership from those who have had little or no Greek (chapter 1: “Structure and Intention of the Edition,” 1–25), to graduate students who have learned Greek and have some comprehension of biblical studies (chapter 2: “Exercises and Learning Aids,” 27–39), to a brief chapter intended for use by “researchers and teachers who interpret the New Testament professionally” (viii), presumably including professors and advanced students (chapter 3: “NA28 as an Edition for Scholars,” 41–54).

Although the second chapter is useful for students, the rationale for the first chapter is puzzling. Why would someone without knowledge of Greek want to use a Greek text at all, especially one as concise (due to the myriad abbreviations, sigla, etc.) and scholarly as the Nestle-Aland? And this being the longest of the three chapters, complete with the Greek alphabet, diphthongs, and other elementary material needed to pronounce ancient Greek, it seems to be a waste of space to some degree. Even in this introductory chapter, Trobisch got some facts wrong. For example, he says that γχ is pronounced ‘nch’ as in ‘anchovies’ (9); the text of the NA28 was produced by “an international editorial committee” (2 [italics added]; see also 49), when the title page indicates only that the Münster institute produced this particular edition; and the canon of the shorter reading or lectio brevior “only applies to two readings that are superficially combined” (24), when the consensus among textual critics is that this rule applies to those variants that have more words than the alternative, whether they are a combination of older readings or not (cf. the variants in John 3:13 and Rom 8:1, for example). Nevertheless, some of the material in the first chapter is helpful for students of Greek. I would recommend eliminating this chapter and combining the best features with what is already in chapter 2.

The second chapter includes helpful information about some of the changes between NA27 and NA28, including the dropping of consistently cited witnesses of the second order, how to use the distinct apparatus for the Catholic Epistles, and a discussion on the Eusebian Canons for the Gospels. On this last item, it should be noted that the Nestle-Aland tradition continues to list the numbers in the Canons as Arabic and Roman numbers. Although this is useful as a tool for the modern student in comparing the Gospels, it is unhelpful for those who spend time on the actual manuscripts, since the Eusebian Canons are found in manuscripts entirely by Greek letters (see https://danielbwallace.com/2014/04/13/conversion-table-for-the-eusebian-canons to download the PDF of a conversion table). This chapter takes the student through the NA28 Introduction, Apparatus, marginalia, and various other features of the book, with exercises sprinkled throughout.

Chapter 3 is a useful introduction to a behind-the-scenes look at the decisions made in Münster concerning the format, text-critical decisions and approach, and differences from the previous edition of the Nestle-Aland text. But Trobisch overstates things when he calls this new edition a “thoroughly revised edition” (vii). To be sure, the apparatus has been thoroughly updated, but the only textual differences are in the Catholic Epistles. Trobisch makes both commendations and criticisms of the 28th edition. In the first section which systematically goes through differences between this and NA27, some of the negative features of the 28th come to light—even though Trobisch explicitly addresses limitations of this new edition in the second section, “Limitations of the NA28.”

Gone are any explicit conjectural emendations, whereas the NA27 listed over 100 of them (one of which was followed [Acts 16:12], though both Bruce Metzger and Kurt Aland disagreed with the rest of the committee), and NA28 adds one more to the text (2 Peter 3:10). (At the same time, neither of the variants in these two passages is a true conjecture since there are versions that have these readings. Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman, The Text of the New Testament, 4th ed. [Oxford: OUP, 2005] 230, implicitly define a conjecture as having no support in Greek manuscripts, versions, or fathers: the need for conjectural emendation for the New Testament is “reduced to the smallest dimensions” because “the amount of evidence for the text of the New Testament, whether derived from manuscripts, early versions, or patristic quotations, is so much greater than that available for any ancient classical author…”)

NA28 also eliminated the useful subscriptions for the NT books found in previous editions, a most unfortunate decision. They have however retained the inscriptions, though Trobisch says that these, too, got the ax (43).

The number of witnesses cited in the apparatus is significantly reduced, and any comparison with previous editions of the Greek NT by Tischendorf, Westcott-Hort, von Soden, and others is eliminated.

The lack of such valuable features means that students and scholars will need to continue using their NA27 in conjunction with NA28. Trobisch notes that 33 textual changes occurred in the Catholic Epistles (44), though there are actually 34 (see NA28, 50*–51* for the list). A brief discussion of the sea-change in Münster from the “local-genealogical method” (which Barbara Aland once told me was not within the bounds of reasoned eclecticism) to the “Coherence-Based Genealogical Method” or CBGM concludes the chapter.

A final criticism of this booklet is that although the author provides links to several sites which host images of NT manuscripts, he overlooks the website for the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (www.csntm.org), which has one of the largest collections of high-resolution digital images of Greek NT manuscripts on the Internet, most of which have been photographed by CSNTM in the last twelve years. Included on this site are images of the Chester Beatty papyri, which CSNTM digitized in the summer of 2013, working with the papyri at the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin.

In sum, I anticipated that this work would be useful for students learning the ropes of NT textual criticism, but the gaps, errata, and proportion leave me somewhat disappointed. Even though there are many helpful features, the work is overall quite uneven. I hope that a second edition which corrects these deficiencies will soon be forthcoming (some of these deficiencies have been corrected in the second German edition of this book), since such a volume is needed for anyone using the Nestle-Aland 28th edition of Novum Testamentum Graece.

Daniel B. Wallace

With the troubles in the world today, especially with ISIS and other groups trying to destroy Christian artifacts, the importance of our work has never been more urgent. And this upcoming expedition will cost CSNTM about $835,000! We need your help. Below are some key items that we will need to pay for. If you believe in the importance of scripture, or even if you are simply interested in making sure that our world heritage is preserved, you need to be involved with CSNTM’s efforts.

With the troubles in the world today, especially with ISIS and other groups trying to destroy Christian artifacts, the importance of our work has never been more urgent. And this upcoming expedition will cost CSNTM about $835,000! We need your help. Below are some key items that we will need to pay for. If you believe in the importance of scripture, or even if you are simply interested in making sure that our world heritage is preserved, you need to be involved with CSNTM’s efforts.  Already in my time in Athens this year, several discoveries have been made. At least half a dozen NT manuscripts—unknown to western scholars—have been discovered. And within other manuscripts, which have been known for well over a century, a number of new and exciting discoveries have been made. CSNTM will have 7–8 people in Athens this summer for over 90 days straight. And we will continue digitizing the manuscripts in 2016. Just some of the equipment costs for this, the largest expedition CSNTM has ever undertaken, are as follows: 1. Four new computers, complete with specialized software, lengthy warranty (we are hard on computers), and fast processors: $18,000 2. Five new cameras, with 50 megapixel imaging capability (each TIFF image will be as many as 300 MB!): $21,000 3. Other equipment needs (including hard drives, onsite RAID system, Graz Travellers Conservation Copy Stand, etc.): $41,000 Total for this equipment: $80,000 On top of this there are housing costs, salaries, training costs, airfare, meals, etc. (I didn’t itemize these because I didn’t want to scare you!) CSNTM will be posting all of the images online so that anyone can see them. The images will be free for all and free for all time.

Already in my time in Athens this year, several discoveries have been made. At least half a dozen NT manuscripts—unknown to western scholars—have been discovered. And within other manuscripts, which have been known for well over a century, a number of new and exciting discoveries have been made. CSNTM will have 7–8 people in Athens this summer for over 90 days straight. And we will continue digitizing the manuscripts in 2016. Just some of the equipment costs for this, the largest expedition CSNTM has ever undertaken, are as follows: 1. Four new computers, complete with specialized software, lengthy warranty (we are hard on computers), and fast processors: $18,000 2. Five new cameras, with 50 megapixel imaging capability (each TIFF image will be as many as 300 MB!): $21,000 3. Other equipment needs (including hard drives, onsite RAID system, Graz Travellers Conservation Copy Stand, etc.): $41,000 Total for this equipment: $80,000 On top of this there are housing costs, salaries, training costs, airfare, meals, etc. (I didn’t itemize these because I didn’t want to scare you!) CSNTM will be posting all of the images online so that anyone can see them. The images will be free for all and free for all time. Another way to look at our costs is to think in terms of digitizing a manuscript. The average NT manuscript will cost CSNTM about $2500 to digitize. That’s about $5.50 per page. Some of you may be able to preserve a few pages; others will be able to preserve a whole manuscript. Every gift counts! And each person who contributes $2500 or more will receive a certificate that specifies how many manuscripts they have digitally preserved. Finally, another way everybody can help is to spread the word. Talk to your friends and family members, link to this blog on your Facebook or other social media, or link to this blog on your own blogsite.

Another way to look at our costs is to think in terms of digitizing a manuscript. The average NT manuscript will cost CSNTM about $2500 to digitize. That’s about $5.50 per page. Some of you may be able to preserve a few pages; others will be able to preserve a whole manuscript. Every gift counts! And each person who contributes $2500 or more will receive a certificate that specifies how many manuscripts they have digitally preserved. Finally, another way everybody can help is to spread the word. Talk to your friends and family members, link to this blog on your Facebook or other social media, or link to this blog on your own blogsite.