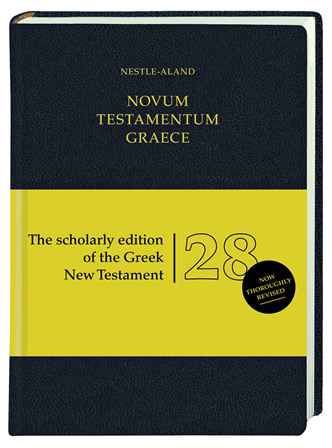

Overview

At the annual Society of Biblical Literature conference held in Chicago last month, the latest edition of the Novum Testamentum Graece, or the Nestle-Aland Greek New Testament, was unveiled. This has been a long time coming—nineteen years to be exact. The Institut für neutestamentliche Textforschung (INTF) in Münster is behind this production, and deserves accolades for its fine accomplishment. This is the first new edition of the Nestle-Aland text since the death of Kurt Aland, the founder of the INTF.

Inexplicably, even though the new text was available at SBL—both as just the Greek text and in diglot with English translations—it could not be acquired through Amazon until later. I pre-ordered a couple copies last April; the diglot arrived in November but the Greek-only text will not be released until January!

Several gave presentations on the new Nestle-Aland text at SBL. Klaus Wachtel of INTF gave an overview of NA28. In his lecture, he noted, inter alia, the following:

- The textual differences from the previous edition only occur in the Catholic Epistles. This is due to the fact that behind the scenes INTF has been doing exhaustive research on many variants in these letters and has produced the impressive Editio Critica Maior (ECM) series. These are the only books that have been thoroughly examined; hence, the changes to the text are only in these books. A total of 34 textual changes have been made.

- In these letters, the siglum Byz is used instead of the gothic M (M).

- As INTF worked through the Catholic letters, they came to see much greater value of the Byzantine manuscripts than they had previously. In Wachtel’s presentation, he noted that the NA27 displayed “prejudice against the Byzantine tradition” while the NA28 recognized the “reliability of the mainstream tradition.” This is a welcome change in perspective, made possible because of exhaustive collations.

- For the entire New Testament, the apparatus functions now as “a gateway to the sources” instead of the more restricted purpose of the previous edition “as a repository of variants.”

The Introduction to the new work adds much more information. Among these consider the following:

- “from now on, the Nestle-Aland will not appear only as a printed book, but also in digital form” (48*). This is more than what is already available in the digital copies of the NA27 that are part of the Accordance and Logos Bible software packages. For example, “Abbreviations, sigla and short Latin phrases in the apparatus are explained in pop-up windows. Above all, the digital apparatus becomes a portal opening up the sources of the tradition, as it provides links to full transcriptions and, as far as possible, to images of the manuscripts included” (48*).

- Gone are the “consistently cited witnesses of the second order”—that is, those witnesses that comprised the gothic M (M) in NA27. Although this siglum is still used, its meaning has changed. Individual non-Byzantine witnesses that are part of the ‘majority text’ (a term that means more than just the Byzantine witnesses in NA27; it is unclear exactly what this siglum means in NA28) are now apparently cited explicitly, even if they agree with the Byzantine minuscules.

- Conjectures are no longer to be found in the Nestle-Aland apparatus. There were nearly 120 conjectures listed in the previous edition. Nevertheless, at Acts 16.12 the editors still print as the text a reading that is not found in any Greek manuscripts (Φιλίππους, ἥτις ἐστὶν πρώτης μερίδος τῆς Μακεδονίας πόλις).

Evaluation

What can we say about this new edition of the Novum Testamentum Graece? First, it is fascinating to see the sea-change going on in Münster. The text of the Catholic Epistles is analyzed on an entirely different basis than the rest of the New Testament. Gerd Mink of INTF has been developing a new textual method called the Coherence-Based Genealogical Method or CBGM. This has been applied only to the general letters to date, but has been in the background of INTF’s work for decades. If this method proves to be worthy of support by other textual critics, it will become another tool—to supplement reasoned eclecticism—that scholars can use to gain greater certainty about the wording of the autographs.

Second, this ‘new’ approach nevertheless has produced some surprising results. Perhaps the most controversial reading in the text of NA28 is found in 2 Peter 3.10: οὐχ εὑρεθήσεται. This is not found in any Greek witnesses. NA27 printed as the text reading εὑρεθήσεται. The textual problem is extraordinarily difficult, and even though εὑρεθήσεται has solid support (א B K P 0156vid 323 1241 1739txt) a variety of variants sprang up most likely because of the difficulty this reading presented.

Another significant change is found in Jude 5. NA27 reads πάντα ὅτι [ὁ] κύριος ἅπαξ, while NA28 has ἅπαξ πάντα ὅτι Ἰησοῦς. The key difference is Ἰησοῦς for κύριος. The text now says that Jesus saved his people out of Egypt and later destroyed the unbelievers. The NET Bible and the ESV also have the reading Jesus. As the primary textual critic for the NET, I felt that this reading would be the most controversial of any that we adopted—if people would ever read Jude! But it seemed to raise no eyebrows at all. One of my students at Dallas Seminary, Philipp Bartholomä, examined the issue in much greater detail, writing his term paper in the class New Testament Textual Criticism on this textual problem. He concluded that Ἰησοῦς was the preferred reading. That paper was developed into an article that was published in Novum Testamentum: “Did Jesus Save the People out of Egypt? A Re-examination of a Textual Problem in Jude 5” (NovT 50 [2008] 143–58).

Third, the massive effort needed to do exhaustive analysis of the witnesses that the ECM displays has resulted in only the Catholic Letters getting a facelift in the apparatus at this stage. NA28 thus offers two different kinds of apparatus—one for the Catholics and one for the rest of the New Testament. This will most likely be confusing to many users, but in order for the edition to come out in a timely fashion this approach was needed. When Acts, John, and the corpus Paulinum receive their own ECM volumes, newer editions of the Nestle-Aland text will no doubt be published. Until then, NA28 will have to do, even though it presents itself as an unfinished work. Meanwhile, Münster will need to generate more literature explaining CBGM in a clear and convincing way.

Fourth, this new text has actually taken a step backward in cooperative effort across ‘denominational’ lines (in a broad sense). The previous edition was edited by three Protestants (Kurt Aland, Barbara Aland, Bruce Metzger), one Roman Catholic (Carlo Martini), and one Greek Orthodox scholar (Ioannes Karavidopoulos). The latest edition lists as its editors only “the Institute for New Testament Textual Research… under the direction of Holger Strutwolf.” This is a surprising development since INTF in the last several years has been partnering with other institutes such as the University of Birmingham (in work on the Gospel of John) and the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts (in utilizing CSNTM’s digital images for much manuscript data). Thus, collaboration is certainly going on, while the final decisions about the text are solely in the hands of Münster.

Finally, regarding the ESV diglot, I have to express my deep disappointment in the format. When the German Bible Society approached Biblical Studies Press about producing a diglot with the NET New Testament, BSP jumped at the opportunity. Three editors worked on the diglot—Michael H. Burer, W. Hall Harris III, and Daniel B. Wallace. Harris in particular should be singled out for his industry in producing an apparatus specifically for the diglot. Besides the translation and text-critical notes already found in the NET New Testament footnotes, Harris added rigorous comparisons with several translations. He ingeniously matched the English page with the Greek—both in the text and footnotes—so that there are no unsightly gaps at the bottom of the page and so that the Greek and English pages correspond to each other. For those textual problems that required longer discussions, an appendix was added. The ESV diglot, on the other hand, leaves gaps on every page that correspond to the Nestle-Aland apparatus. The whole endeavor looks as though it was hurriedly put together. Another diglot is soon to appear: the NRSV and REB with the NA28. I have not yet seen this volume, but my hunch is that the two English translations will stand side-by-side in columns that will extend to the bottom of the page, thus corresponding to the Greek. This will almost surely be more aesthetically pleasing than the ESV diglot.

Overall, Nestle-Aland28 is a welcome addition for students of the Greek New Testament. Not only a welcome addition, but a necessary one for those who wish to stay current on the critically-reconstructed text of the New Testament. And it makes a great Christmas present for seminary students, pastors, translators, and professors. It’s available at Amazon in a variety of versions: Greek text only, Greek text with dictionary, and diglot.

Many thanks for this very helpful post!

Incidentally, there is a sample page of the forthcoming NA28/REB/NRSV Greek-English New Testament at the very bottom of this page in the NA28 website:

http://www.nestle-aland.com/en/extra-navigation/druckausgaben/

The English translations will indeed be printed in parallel columns, but it appears that there will also be gaps on every page corresponding to the apparatus..

LikeLike

It’s unfortunate that the sample page seems to be little different from the NA28-ESV diglot in terms of the big gap at the bottom of the English side.

LikeLike

Thanks for all the great info on NA28 Dan! I love that they put “Jesus” back into the text of Jude 5 where it belongs. I had come across this quote from Justin Martyr which, even if this is not direct quote of Jude 5, it clearly shows the early Christians were fine with saying Jesus led His people out of Egypt. “For all we out of all nations do expect not Judah, but Jesus, who led your fathers out of Egypt” (Dialogue with Trypho, 120)

LikeLike

Justin, your work in patristics is inspiring!

LikeLike

I am only an interested layman, but I certainly noticed Jude 5 in my ESV. It seems theologically/apologetically significant to me in terms of understanding the Trinity.

On a related note — I would’ve loved to have been in the crowd to see the facial expressions when Jesus uncorked his words from John 5:39 and 5:46:

“You search the Scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is they that bear witness about me…”

“For if you believed Moses, you would believe me; for he wrote of me.”

LikeLike

Also of note: Stan Helton has analyzed the differences between NA27 and NA28 in the Catholic Epistles at his blog, Stan’s Scholia.

Yours in Christ,

James Snapp, Jr.

LikeLike

Where might I find Stan’s Scholia James?

LikeLike

Whereas I would have liked to see the ESV have an apparatus of sorts, the gaps do allow space for more notes – which isn’t a bad thing.

LikeLike

Pingback: Dan Wallace on NA28 « Michael H. Burer

Pingback: What NA28 May Mean For the Future of Reasoned Eclecticism | Brian J. Lund

Dr. Wallace,

Thank you for the summary and evaluation. I am surprised about the editors’ decision concerning M vs. Byz.

Blessings!

ECR

LikeLike

Reblogged this on A Man from Issachar.

LikeLike

Dr. Wallace, could you perhaps comment more on the 2Pet 3.10 insertion of ουχ? I’m no text-critic, but from the NET note on this verse I see that this inclusion of the negative particle is supported by the Sahidic MSS—so any idea on what tipped the scale for the NA28 editors towards this reading?

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Vanitas Vanitatum and commented:

NA28

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Marius Cruceru and commented:

Noutați pentru studenții Clasei de Limba Greacă a Noului Testament

LikeLike

Pingback: A Complementarian’s list of the top Christian books for 2012, and Barbara Aland

The white space in the ESV diglot looks great for note taking!

LikeLike

I’m interested in your comment about the changes made in favor of the Byzantine tradition, since people like Maurice Robinson have been arguing that way for a while. Are there any areas where the NA28 now uses a primarily Byzantine reading?

LikeLike

Dear Dr Wallace, thanks for this info,I am a frequent visitor in your website, how about this Greek – Eng edition for believers like me who do not know Greek? Do you recommend this edition for devotional reading purpose?

LikeLike

Pingback: Keep ‘em coming back with the December Biblical Studies Carnival | Words on the Word

Pingback: Nestle-Aland 28: The New Standard in Critical Texts of the Greek New Testament | Greek Language and Linguistics

With its extensive, differentiated apparatus, above all the Novum Testamentum Graece by Nestle-Aland enables its readers to reach their own judgments in matters of New Testament textual research. The Greek New Testament , on the other hand, is not intended as an aid to extensive text-critical research, but above all provides the foundation for translations of the New Testament worldwide. It presents to its users a reliable Greek text, and for selected passages elucidates the course of its development.

LikeLike

The apparatus is not at all “extensive.” Its very small in comparison even to apparatai from the 1800slike Tischendorf’s 8th. Nestle-Aland is a joke. And its text is produced simply for agnostics like Bart Ehrman, or rather to make more of them.

LikeLike

I have an older version of the Interlinear – Would l notice a difference if l bought a new version?

LikeLike

Pingback: Jesus Saved Israel from the Egyptians | David Knopp

Pingback: Words on the Word | The Bible You Would Have Brought to Your 3rd Century Church Service

Pingback: Barbara Aland and the Nestle-Aland Greek NT

Pingback: Who Wrote the Bible? (Part 4) | Veracity

Pingback: The Thistle // Covenant Theological Seminary – Library Acquisitions for December 2012 & January 2013

as regards Jesus or the Lord leading them out of Egypt, isn’t it just possible that because Jesus/Joshua are effectively the same word underneath it all that it was Joshua who led them out of Egypt and later destroyed those who did not believe. both names essentially meaning HaShem who saves.

LikeLike

Can you help me? Do you know: what computers or softwares do the use for textual criticism on Munster? IS there any website about this topic?

LikeLike

Pingback: Resposta a uma crítica a respeito de Mateus 13:39 na TNM | Tradução do Novo Mundo Defendida!

Pingback: Barbara Aland and the Nestle-Aland Greek NT | Marg Mowczko